Concurrent delays frequently occur in construction projects, especially in complex construction projects in which various contracting parties implement and are responsible for a variety of activities over the project life cycle. Assessing concurrent delays is among the most challenging forensic delay analysis practices because, contractual, legal, and technical considerations add several layers of complexity to cases of concurrent delays.

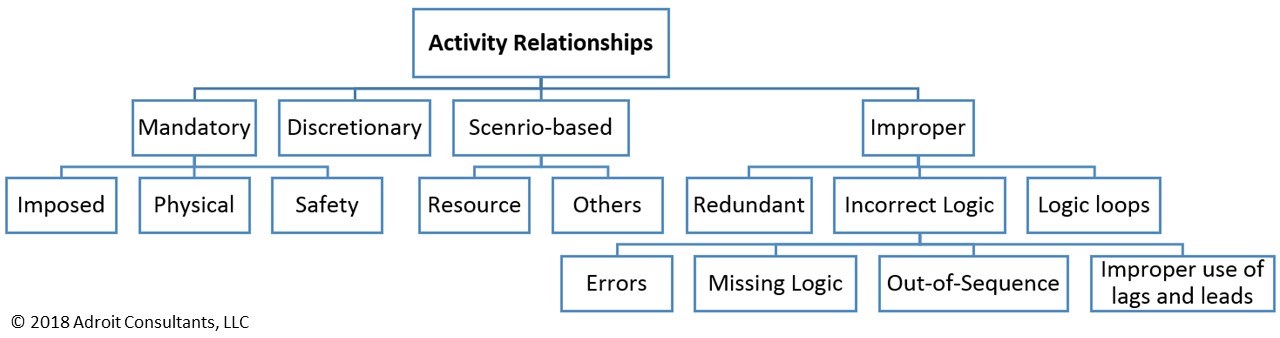

A project network not only contains project activities but also defines activity dependencies (also known as activity ties or activity relationships). Two or more delayed activities in a project network may be identified to be concurrent when they, partly or wholly, overlap one another. Therefore, a project network is a key tool to identify what activities partly or wholly overlap and what their dependencies are. Courts, boards of contract appeals, and experts, however, are inconsistent in their approach to defining concurrent delays.

Definitions

Experts rely on different references for the definition of concurrent delays. In the United States, one of the technical references that is commonly-cited in delay claims is AACE International Recommended Practice (RP) 10S-90, entitled Cost Engineering Terminology. RP 10S-90, however, does not offer one single definition of concurrent delays. Two of these definitions are provided below (AACE International, 2017, p. 21);

(1) Two or more delays that take place or overlap during the same period, either of which occurring alone would have affected the ultimate completion date.

(2) Concurrent delays occur when there are two or more independent causes of delay during the same time period. The “same” time period from which concurrency is measured, however, is not always literally within the exact period of time. For delays to be considered concurrent, most courts do not require that the period of concurrent delay precisely match. The period of “concurrency” of the delays can be related by circumstances, even though the circumstances may not have occurred during exactly the same time of period.

Another commonly-cited technical reference is AACE International RP 29R-03, entitled forensic schedule analysis. RP 29R-03 identifies that the following tests must be proven to ensure concurrent delays exist (AACE International, 2011):

- Two or more unrelated, independent delays exist. One of these delays can a delay arisen from a force majeure event.

- None of the delays identified in Step 1 can be a voluntary delay.

- Not all delayed activities identified in Step 1 are the responsibility of only one contracting party.

- The project completion date would have been delayed in the absence of any of the delays identified in Step 1.

- The delayed work has to be substantial (i.e., not easily correctable).

The meaning of concurrent delay is different in the English Law. The following are two excerpts that help illustrate the meaning of concurrent delay under the English law:

- True concurrent delay is the occurrence of two or more delay events at the same time, one an Employer Risk Event, the other a Contractor Risk Event, and the effects of which are felt at the same time… In contrast, a more common usage of the term ‘concurrent delay’ concerns the situation where two or more delay events arise at different times, but the effects of them are felt at the same time. In both cases, concurrent delay does not become an issue unless each of an Employer Risk Event and a Contractor Risk Event lead or will lead to Delay to Completion. Hence, for concurrent delay to exist, each of the Employer Risk Event and the Contractor Risk Event must be an effective cause of Delay to Completion (not merely incidental to the Delay to Completion) (The Society of Construction Law, 2017).

- Concurrent delay is used to denote a period of project overrun which is caused by two or more effective causes of delay which are of approximately equal causative potency (Marrin, 2012).

Entitlements

Concurrent delays typically entitle contractors to time extension, but not time-related delay damages. In other words, if a contractor is able to demonstrate the presence of concurrent delays, it may be entitled solely to time extension for the net period of the concurrent delay.

It is important to note that in some cases, two or more delays occur concurrently (overlap one another to some extent), all of which are the responsibility of one single contracting party. In that case, the net effect of the concurrent delays have to be taken into account in assessing delays. For instance, if two overlapping 5 day owner-caused delays exist, entirely overlapping each other, the contractor is only entitled to a single 5-day time extension. As another example, if a contractor is found to be responsible for a 10-day delay, 7 of which are concurrent with another contractor-caused delay, the contractor is ultimately responsible for 10 days of delay, not 17 days.

In a similar way, if both an owner and a contractor concurrently contribute to the occurrence of a critical path delay (i.e., a delay that ultimately results in the delay of the project completion date), none of the contracting parties is typically entitled to collecting delay damages from the other party unless delay responsibilities can be apportioned between the parties.

In the event of a concurrent delay, the time impact of a contractor-caused delay on a project’s longest path may be greater in magnitude than the time impact of an owner-caused delay. Under such circumstances, it is sound to expect that the owner is entitled to collect delay damages for the excess impact. Conversely, the time impact of an owner-caused delay on a project’s longest path may exceed the time impact of a contractor-caused delay. Thus, it is critical to perform forensic schedule analysis and closely examine the cases of concurrency to properly allocate responsibilities for delays and specify proper entitlements.

Although definitions of concurrent delays exist in the literature, any assessment of concurrent delays has to start with performing a liability analysis (i.e., entitlement assessment) based on contractual rights and duties of contracting parties. Performing such liability assessments is necessary because the contract may specify how the cases of concurrency are characterized and how they are supposed to be assessed and/or dealt with.

The lack of clear contractual procedures for concurrent delays increases the likelihood of delay-related disputes. As noted above, courts, boards of contract appeals, and experts are inconsistent in their approach to characterizing and assessing concurrent delays. Therefore, it is important that the parties exercise due diligent in preparing unambiguous contract language that facilitates successful resolution of delay-related matters before they result in a conflict.

Moreover, if a party is in a position to negotiate over the provisions of a contract, it is recommended that it negotiates to reach an agreement, prior to signing the contract, on definitions of and procedures for assessing various types of delays including concurrent delays. Such definitions and procedures combined with the use of sound forensic schedule analysis techniques can play key roles in minimizing and/or successful resolution of delay-related disputes.

References:

AACE International. (2011). Recommended Practice No. 29R-03 Forensic Schedule Analysis. Morgantown, WV, USA: AACE International®.

AACE International. (2017). Recommended Practice No. 10S-90 Cost Engineering Terminology. Morgantown, WV, USA: AACE International®.

Marrin, J. (2012). Concurrent Delay Revisited 2. Presented at the Society of Construction Law Meeting, London, England (December 4, 2012).

The Society of Construction Law. (2017). Delay and Disruption Protocol, 2nd edition (DDP2). Retrieved from https://www.scl.org.uk/sites/default/files/SCL_Delay_Protocol_2nd_Edition.pdf

Author: Dr. Amin Terouhid, PE, PMP, PSP | Principal Consultant

Amin Terouhid is a construction claims expert and a Principal Consultant with Adroit Consultants, LLC. He was a recipient of the 2018 AACE Technical Excellence Award.

Note: If you are interested to find out more about the main considerations in assessing concurrent delays, please contact us. Adroit’s consultants have demonstrated their expertise in performing delay analysis and will be able to assist. You may also be interested to read the following articles:

Adverse effects of schedule deficiencies on claim administration